Puppets Rule the Street

Young lawyer Rania Refaat uses puppet shows to educate people on the streets of Cairo about their legal rights and responsibilities.

“The sheltered nobleman’s daughter, whom you thought to be an angel, turned out to be a malicious leech … discord will be man’s downfall and perdition…” – thus goes the gloomy moral of the story El-Bint Beta. A girl named Beta spies on her fellow villagers, unearthing their secrets. She is banished, yet tries to make amends for her mistakes.

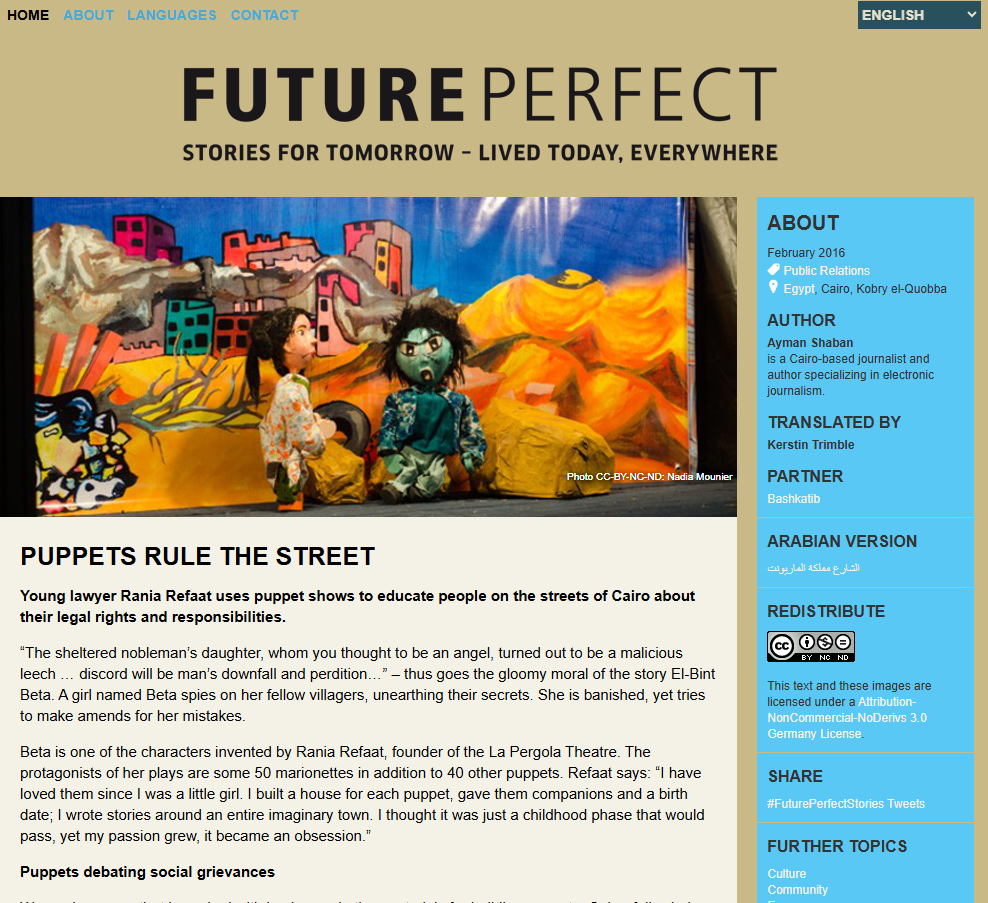

Beta is one of the characters invented by Rania Refaat, founder of the La Pergola Theatre. The protagonists of her plays are some 50 marionettes in addition to 40 other puppets. Refaat says: “I have loved them since I was a little girl. I built a house for each puppet, gave them companions and a birth date; I wrote stories around an entire imaginary town. I thought it was just a childhood phase that would pass, yet my passion grew, it became an obsession.”

Puppets debating social grievances

We are in a room that is packed with lumber and other materials for building puppets. Colourfully clad marionettes are hanging from the walls, others are still being assembled. As crammed as this room may be, it holds vast worlds of creativity, art and discovery for its heroes Samaka, Akwa, Beta, Umm Beta, Ali Bazzaza and many others. The story of the La Pergola street theatre began with a desire to raise citizens’ awareness for their own problems, explore them on the street and stir a debate among the audience that would eventually lead to solutions. According to Refaat, art is a gentle, yet powerful agent of change. To her, the theatre she launched in 2011 is one that creates awareness.

Her first puppet show with the title Open Your Eyes, Iss Melban was about political education and premiered at a bus stop in the Greater Cairo district of Road El-Farag/Shubra. The second play, The Street is a Kingdom, Brother, dealt with the topic of street children and was performed at the El-Buha stop in Imbaba (Giza Governorate). Another production, The Land of Black and White, addressed the trash problem in Egypt and was presented at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. To date, the theatre has put on about 60 shows.

“To keep Egypt from becoming one big prison”

Refaat tells us that following each performance, they interact with the audience by leading an open discussion. Audience members who participate in the debate can even win prizes. The dialogue helps discover the roots of a problem together, raising awareness in children and adults alike. “To keep Egypt from becoming one big prison,” Rania Refaat replies when asked why she chose the street as the venue for her plays. She adds: “On the street, you reach the majority of a society, and we want to address everyone. We are an alternative to having no cultural life in Egypt at all.”

Rania Refaat is actually a lawyer by trade, yet she feels that her original line of work is not very helpful in addressing the issues she cares about – issues of rights and liberty. Her clients usually couldn’t afford to pay for a lawyer. She hopes to one day cure “legal illiteracy” with interactive performances that teach about the law as well as civil rights and responsibilities.

The 2015 Rule of Law index of the World Justice Project ranks Egypt as number 86 of a total of 102 countries. In addition, a new United Nations report lists the country among the ones with the highest illiteracy rates in the Arab region and number 10 in the world.

“There is no culture in Egypt”

“The Ministry of Interior is terribly afraid of the arts and would rather see us go back home,” Refaat states what she considers the greatest challenge for La Pergola. Since the events of June 30th, 2013, which led to the fall of the Muslim Brotherhood and Muhammad Mursi, and the rise of General Abd al-Fattah as-Sisi as the new President, security measures have imposed stark limits on the project. She adds that political obstacles and red tape, as well as a poor cultural climate in Egypt, bar her from public theatres and from receiving any funding from the General Authority for Cultural Palaces (Qusur ath-Thaqafa).

According to theatre critic Dr. Huda Wasfi, street theatre is a form of independent theatre, which is still passed over by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture. This lack of support has plunged the theatre scene into a genuine crisis: Many ensembles simply disappear; some artists are forced to turn their backs on theatre and find another venue. Wasfi demands that the state make part of the Qusur ath-Thaqafa budget available to independent small-scale productions.

Chased away by Salafists

The founder of La Pergola tells how the group, which consists of both men and women, was once attacked by stone-throwing Salafists during a performance at a bus stop in Shubra El-Kheima. Followers of this conservative strand of Islam want genders to be strictly separated.

Refaat also laments that Egyptian society does “not respect work”: Members of her team do not show up on time, show little motivation to learn new things and do not follow through on their tasks. She had to set benchmarks to determine who can join La Pergola. In the meantime, she has gathered a group of 15 men and women who take care of the different tasks, from production to scriptwriting, animation and voicing the parts.

The biggest challenge for the project, however, is funding. Refaat finances the plays herself, even though she states that a seven-month production costs about 50,000 EGP, the equivalent of over 6,000 US Dollars. Since she is “soon going to be broke”, she has reached out to sponsors. She will only accept money on the condition that the sponsor will not “interfere with the contents”.

Refaat’s dream is to open a theatre academy. She also hopes to be minister of culture three years from now. She wants to help Egyptians live in happiness and freedom – unlike the way it was under Mubarak, who tried to destroy her countrymen’s dreams. “We can’t afford to die a second time,” says Rania Refaat